News

Cash prevents social upheaval

Sunday, February 04, 2018

View Showroom

By Currency Research

As noted by the UK Payments Council, cash “is regarded as a public good by its users.”62 A recent survey by Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology found that two-thirds of Swedish citizens perceived cash as a human right.63 Furthermore, it is the only tangible connection between citizens and the Central Bank. Without physical currency, most citizens would be left with only the most abstract notions of Central Bank policy framework and financial stability regulations.

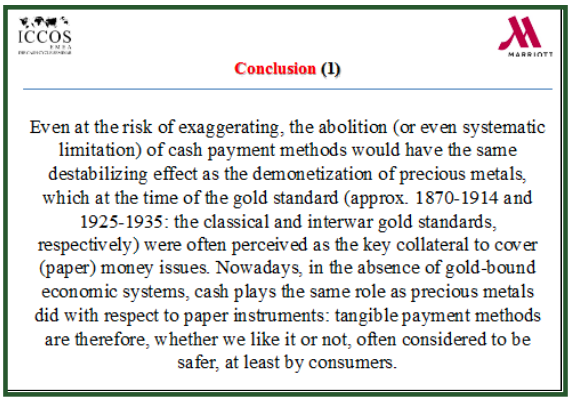

Dr. Beretta, in his 2015 ICCOS EMEA presentation in Milan, remarked on the potentially destabilizing effect the abolition of cash would have on society:

In anthropologist J.A. Dickinson’s essay, “Changing Money in Post-Soviet Ukraine,” the expressive power of cash is examined; specifically, she explores how currency can serve as a diagnostic tool for citizens to evaluate a government’s efficacy and legitimacy. Dickinson suggests that the stability and availability of a national currency is tightly interwoven with citizens’ perception of government credibility and collective national identity:

At a November 2014 conference in Cape Town, Francis Groepe, Deputy Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, warned of the risks associated with reducing cash production and use. According to Groepe, the Central Bank’s duty is to ensure stability and the smooth functioning of the economy. Disruption in cash management can lead to socio-political instability, which in turn can lead to more financial instability and its repercussions:

In his May 2014 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper, “Costs and Benefits to Phasing out Paper Currency,” Kenneth S. Rogo also points out this risk:

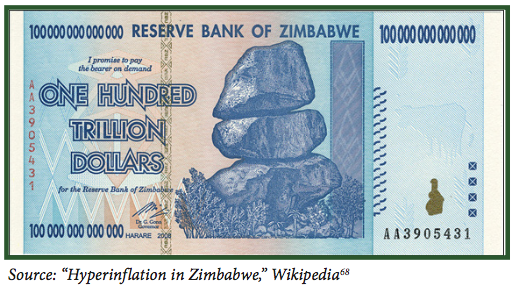

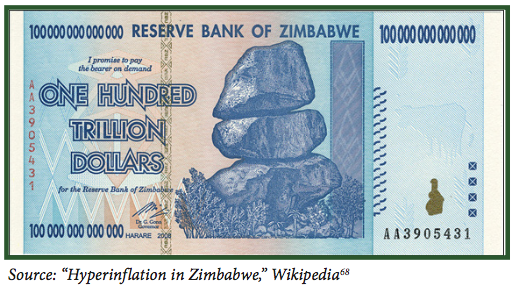

During a period of prolonged currency instability and hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, when public trust of the Central Bank and the national currency were waning, the Zimbabwean government deliberately underreported currency circulation statistics to prevent citizen unrest and social upheaval. In the midst of this crisis, in 2004, the Zimbabwe Independent reported on the doubtful legitimacy official money supply and inflation statistics released by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe:

A widespread lack of confidence in the Central Bank and the national currency continue to this day in Zimbabwe. In 2012, when the government floated the idea of currency reforms and a return to the Zimbabwean dollar, many predicted an upsurge in citizen unrest.

As reported by the Inter Press Service (IPS) News Agency in 2012, the reintroduction of the “Zim dollar” posed a significant risk of street protests, boycotts, and general upheaval:

Throughout history, failed economies have been tied to failed banknotes, inflation, and social upheaval, usually resulting in an eventual return to a “new” national currency. From Rome to Iran, loss of trust in the local currency has historically led to social unrest.

In a 2012 article about hyperinflation in Iran, Marin Katusa comments on the inextricable relationship between currency debasement and social upheaval:

Similarly, a 2013 Globe and Mail article describes the link between currency woes in the euro zone and the current political and social crisis spreading throughout the region:

Central Banks must maintain trust in order to maintain economic stability, thereby preventing unrest. Any disruption to services provided by a nation has the inherent potential to spark social unrest; taking away a trusted, efficient, convenient, and safe national symbol like cash would be akin to dismantling the Central Bank itself. This could cause disruption to both trade and finance, which then, as evidenced above, has the potential to cause significant social and economic upheaval.

This article has been posted with permission from Currency Research and is excerpted from The Case for Cash Part 2: The Justification. To request a copy of the full report or to learn more about Currency Research, please click here.

62 http://www.paymentscouncil.org.uk/files/payments_council/future_of_cash2.pdf

63 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/11/welcome-sweden-electronic-money-not-so-funny

64 J.A. Dickinson, “Changing Money in Post-Soviet Ukraine,” in Money: Ethnographic Encounters, Eds. Stefan Senders and Allison Truitt, Berg: New York, 2007.

65 https://www.resbank.co.za/Publications/Speeches/Pages/SpeechesbyGovernors1.aspx

66 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20126.pdf

67 http://www.theindependent.co.zw/2004/03/12/money-supply-up-now-8626/

68 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperinflation_in_Zimbabwe

69 http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/01/woe-betide-the-return-of-the-zimbabwean-dollar/

70 http://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Could-Social-Upheaval-in-Iran-Spark-an-Oil-Bull-Market.html

71 www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/next-phase-in-euro-zones-woes-political-upheaval/article11427053/

As noted by the UK Payments Council, cash “is regarded as a public good by its users.”62 A recent survey by Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology found that two-thirds of Swedish citizens perceived cash as a human right.63 Furthermore, it is the only tangible connection between citizens and the Central Bank. Without physical currency, most citizens would be left with only the most abstract notions of Central Bank policy framework and financial stability regulations.

Dr. Beretta, in his 2015 ICCOS EMEA presentation in Milan, remarked on the potentially destabilizing effect the abolition of cash would have on society:

In anthropologist J.A. Dickinson’s essay, “Changing Money in Post-Soviet Ukraine,” the expressive power of cash is examined; specifically, she explores how currency can serve as a diagnostic tool for citizens to evaluate a government’s efficacy and legitimacy. Dickinson suggests that the stability and availability of a national currency is tightly interwoven with citizens’ perception of government credibility and collective national identity:

[The] promise of a national currency was not just about the credibility of the post-Soviet Ukraine government; it was also about the meaning of change symbolically expressed in valuations of the many currencies circulating in the markets, in people’s memories of the past and their visions of the future.64

At a November 2014 conference in Cape Town, Francis Groepe, Deputy Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, warned of the risks associated with reducing cash production and use. According to Groepe, the Central Bank’s duty is to ensure stability and the smooth functioning of the economy. Disruption in cash management can lead to socio-political instability, which in turn can lead to more financial instability and its repercussions:

Following the Great Recession, most central banks had either their mandate expanded or their mandate was more explicitly defined to include financial stability. The supply and availability of cash is a critical component of financial stability because a shortage of physical cash can lead to socio-political instability which may result in spill-over effects. Hence, it is important that central banks approach and treat cash management with the same diligence as they treat their monetary and financial stability mandates, as it does not stand separate from those mandates, but in fact is a key component of those mandates.65

In his May 2014 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper, “Costs and Benefits to Phasing out Paper Currency,” Kenneth S. Rogo also points out this risk:

But it is important to acknowledge that there is a least an outside risk that if the government is too abrupt is abandoning a century-old social convention, it will destabilize inflation expectations, introduce a risk premium into bond pricing, and generally induce unexpected macroeconomic instabilities.66

During a period of prolonged currency instability and hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, when public trust of the Central Bank and the national currency were waning, the Zimbabwean government deliberately underreported currency circulation statistics to prevent citizen unrest and social upheaval. In the midst of this crisis, in 2004, the Zimbabwe Independent reported on the doubtful legitimacy official money supply and inflation statistics released by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe:

“It’s an understatement,” said John Robertson, commenting on the new money supply figure. “The figure does not include the $120 trillion printed to buy foreign currency to pay the IMF (International Monetary Fund)."

Robertson’s comment reinforced entrenched fears among economic players that official money supply growth figures, as well as inflation figures, have been understated by a bureaucratic system to understate the gravity of the country’s economic woes and subdue any potential for social upheaval.67

A widespread lack of confidence in the Central Bank and the national currency continue to this day in Zimbabwe. In 2012, when the government floated the idea of currency reforms and a return to the Zimbabwean dollar, many predicted an upsurge in citizen unrest.

As reported by the Inter Press Service (IPS) News Agency in 2012, the reintroduction of the “Zim dollar” posed a significant risk of street protests, boycotts, and general upheaval:

For political analyst and academic Donald Sithole, the return of the Zimbabwean dollar could be a recipe for social upheaval.

“We have seen it elsewhere, disgruntled masses taking to the streets not because of political grievances but increasingly to demand economic justice, and the history of the Zimbabwe dollar era could point to the return of worse strife for ordinary people,” Sithole told IPS.69

Throughout history, failed economies have been tied to failed banknotes, inflation, and social upheaval, usually resulting in an eventual return to a “new” national currency. From Rome to Iran, loss of trust in the local currency has historically led to social unrest.

In a 2012 article about hyperinflation in Iran, Marin Katusa comments on the inextricable relationship between currency debasement and social upheaval:

In the third century, greed got the best of Rome’s emperors. As they spent through the silver in the treasury, one emperor after another reduced the amount of precious metal in each denarius until the coins contained almost no silver whatsoever.

It was the world’s first experience with currency debasement and hyperinflation. As people saw the value of their savings evaporate, society grew angry and demanded a scapegoat. Christians became that scapegoat, and Romans turned on them with incredible violence.

This pattern – currency debasement leading to social upheaval and violence – would repeat many times over.

In medieval Europe, the number of women on trial for witchcraft climbed in sync with the debasement of currency. In revolutionary France, the Reign of Terror that slaughtered 17,000 wealthy counterrevolutionaries aligns perfectly with the deterioration of the purchasing power of the assign at note.

And in the most vile example: dramatic hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s allowed Hitler to rise to power by blaming Jews for the country’s economic woes.

The connection between currency debasement and social upheaval makes sense – hyperinflation only occurs in times of domestic drama. ...

That brings me to today... and to Iran, where that volatile mix of domestic drama and hyperinflation is pushing a fragile society to the brink of revolution.

If history repeats itself and Iran descends into revolution, the outcome is both unclear and obvious...

On October 3, riot police converged on Tehran’s Grand Bazaar. With water cannons and batons, they dispersed a large crowd of demonstrators who were calling President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad a traitor for his mismanagement of Iran’s economy.

The spark that lit the protest flame this time? The Iranian rial had lost a third of its value against the dollar in the three previous days. 70

Similarly, a 2013 Globe and Mail article describes the link between currency woes in the euro zone and the current political and social crisis spreading throughout the region:

Is the euro crisis over? Depends on how you define “crisis.” If you define it as an existential threat to the currency, it’s pretty much over. But if you define it as a political and social crisis, this pig has legs.

The euro zone has entered Stage Two of the crisis, political upheaval. It might be followed by Stage Three, social upheaval, before the next generation of politicians finds something workable to keep the euro zone more or less intact.71

Central Banks must maintain trust in order to maintain economic stability, thereby preventing unrest. Any disruption to services provided by a nation has the inherent potential to spark social unrest; taking away a trusted, efficient, convenient, and safe national symbol like cash would be akin to dismantling the Central Bank itself. This could cause disruption to both trade and finance, which then, as evidenced above, has the potential to cause significant social and economic upheaval.

This article has been posted with permission from Currency Research and is excerpted from The Case for Cash Part 2: The Justification. To request a copy of the full report or to learn more about Currency Research, please click here.

62 http://www.paymentscouncil.org.uk/files/payments_council/future_of_cash2.pdf

63 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/11/welcome-sweden-electronic-money-not-so-funny

64 J.A. Dickinson, “Changing Money in Post-Soviet Ukraine,” in Money: Ethnographic Encounters, Eds. Stefan Senders and Allison Truitt, Berg: New York, 2007.

65 https://www.resbank.co.za/Publications/Speeches/Pages/SpeechesbyGovernors1.aspx

66 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20126.pdf

67 http://www.theindependent.co.zw/2004/03/12/money-supply-up-now-8626/

68 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperinflation_in_Zimbabwe

69 http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/01/woe-betide-the-return-of-the-zimbabwean-dollar/

70 http://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Could-Social-Upheaval-in-Iran-Spark-an-Oil-Bull-Market.html

71 www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/next-phase-in-euro-zones-woes-political-upheaval/article11427053/

Additional Resources from ATM Industry Association

- 4/26/2024 - Time to Take Action! Support the Crime Bill - We Need You!

- 4/23/2024 - ATMIA Unveils Strategic Collaboration with Reconnaissance International to Elevate Intelligence & Networking Services to the ATM & Currency Industries

- 4/21/2024 - Fight Against Cashless Economy:

- 4/18/2024 - 3 myths about accepting cash at self service

- 4/18/2024 - Upcoming ATMIA/ASA Committee Meetings: April and May 2024

- Show All ATM Industry Association Press Releases / Blog Posts