News

Myth: Only criminals use banknotes

Friday, May 19, 2017

View Showroom

By Currency Research

The card industry’s sensational claim that cash use implies criminality, whether made explicitly or implicitly, is extremely arrogant and overwhelmingly based upon faulty or biased research. The correlation between criminal acts and cash use has been made many times by individuals with ties to other methods of payment, typically credit and debit cards, to convince central banks and governments to abandon cash.

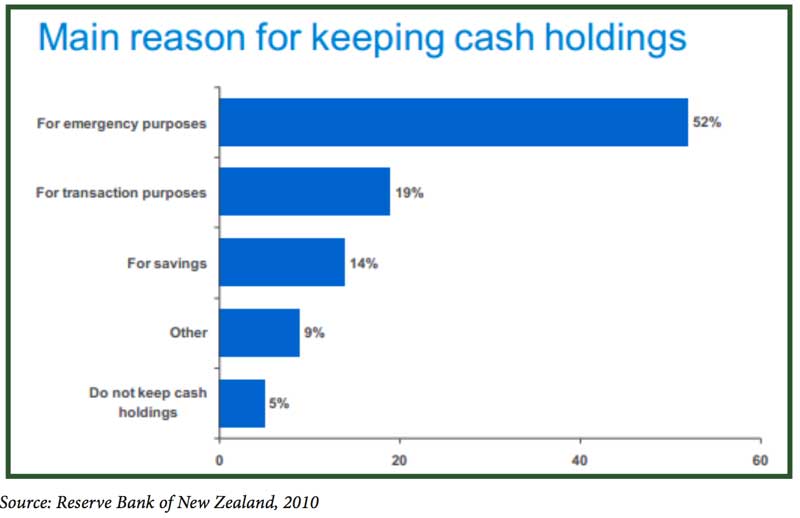

What this claim does not take into account is the number of unbanked and underbanked individuals and households that rely on cash for everyday transactions, as well as stored value. Central bank payment studies from around the world, including the New Zealand study referenced below, have clearly shown that a majority of people continue to use cash every day for a number of perfectly legitimate and logical reasons, whether they be emotional, historical, or logical. In times of uncertainty, there is no equal to cash as a stored value.

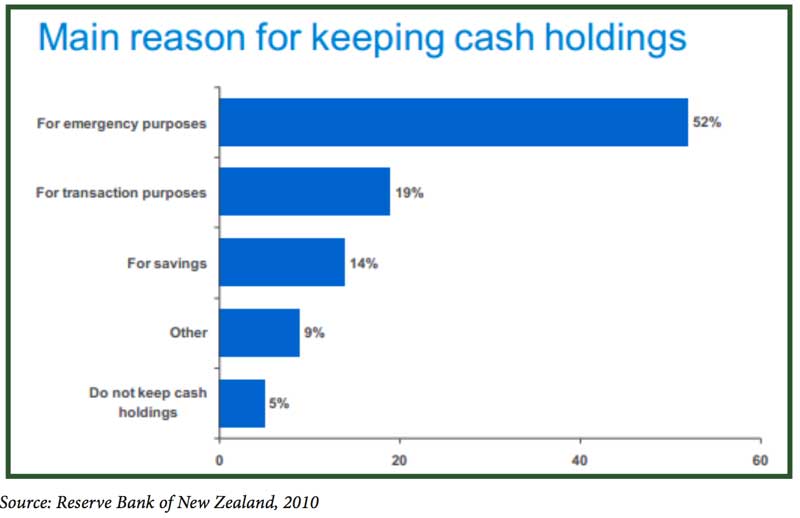

A 2010 consumer study by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, recently presented at a Currency Conference, found that only 5% of New Zealanders did not hold cash. 102 The conclusion that 95% of New Zealanders are criminals or engaged in criminal behaviors would be false!

For unbanked and underbanked individuals, as defined below by Martha Perine Beard in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Central Banker, cash is a must for day-to-day living:

A sizeable percentage of the global population does not have a bank account or use formal financial services. Currency Research looks at the numbers of unbanked and underbanked individuals in the US and around the world.

The 2011 US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households found that over 28% of US households are considered unbanked or underbanked and 42.9% have used alternative financial services (AFS):

Forbes reported on the FDIC survey cited above in 2013:

Central Banker reports that the percentage of unbanked individuals has remained relatively constant at 9% of the total American population from 2001 to 2009. 106

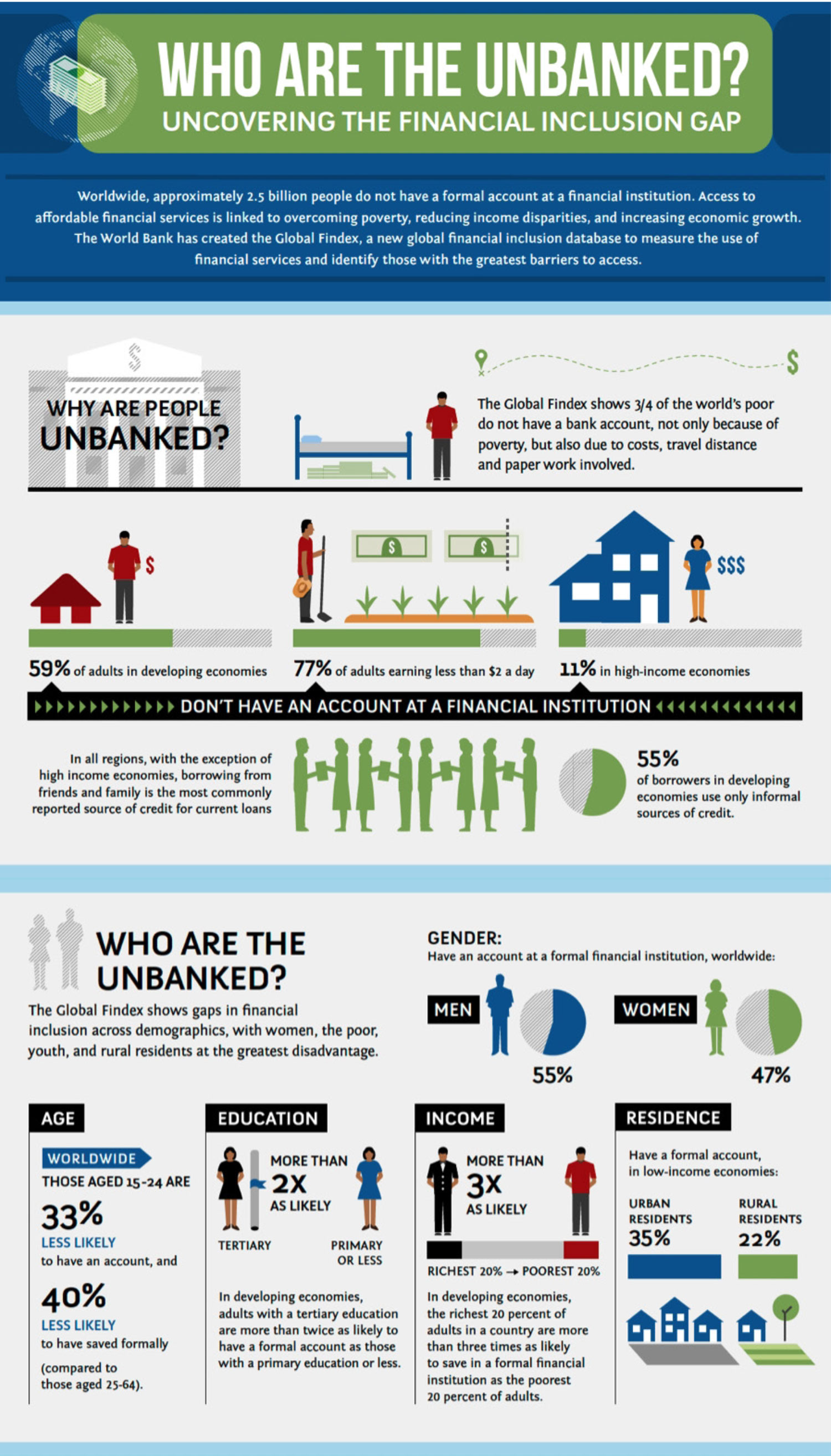

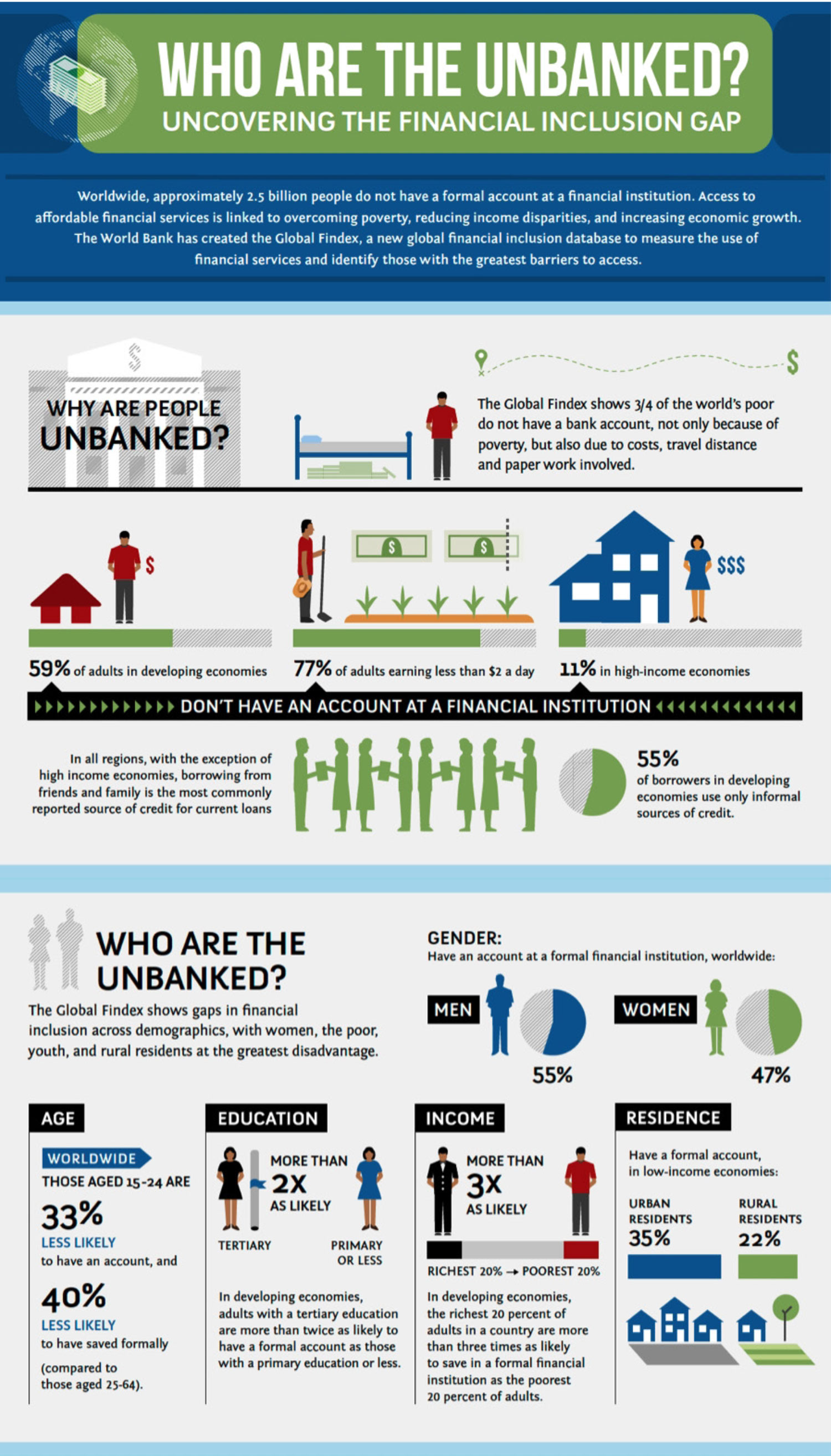

According to a 2011 World Bank survey, over 2.5 billion people around the world are unbanked (this figure does not include the underbanked):

The infographic on the following page presents data about the world’s unbanked sourced from the World Bank’s Global Findex, a global financial inclusion database that measures the use of financial services and identifies the unbanked, a category which includes those who experience the greatest barriers to access. 108

According to the Central Bank of Ireland’s 2013 National Payments Plan, the unbanked in Ireland include a range of financially excluded groups that rely on cash on a daily basis for a variety of legitimate reasons:

In times of economic upheaval, cash remains indispensible as a stored value. As shown in the article below, American financial advisors advise clients to hold as much as eight months’ worth of living expenses in cash at all times:

To underscore this point, the chairman of Currency Research opened the 2013 Currency Conference in Athens with the slides below. The slides detail the chairman’s recent personal experience in Cyprus on the day the banking system failed and cash became king for months:

In times of economic crisis when banks, electrical, and even mobile systems fail, cash is the only truly reliable method of payment. For contingencies on how to move cash and maintain economic stability during such upheavals, central banks are among the most prepared institutions in the country. Unfortunately, there are many recent and historical examples of the role of central banks in averting economic meltdowns.

Currency Research disagrees with the sensationalist and false claim that cash use implies criminal behavior. Diverse groups of people use cash for a range of legitimate reasons, as noted in the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s 2010 consumer study cited above, with large denominations typically reserved for stored value and small denominations used for everyday transactions.

This article has been posted with permission from Currency Research and is excerpted from The Case for Cash Part 1: Myths Dispelled. To request a copy of the full report or to learn more about Currency Research, please click here.

102 http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/notes_and_coins/banknote_upgrade/4436446.pdf

103 https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/cb/articles/?id=2039

104 http://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2013_AFSAddendum_web.pdf

105 http://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2013/06/14/banking-the-unbanked-a-how-to/

106 https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/cb/articles/?id=2039

107 http://go.worldbank.org/72MAKHBAM0

108 http://go.worldbank.org/QMN11VEEX0

109 https://www.centralbank.ie/paycurr/paysys/Documents/National%20Payments%20Plan%20-%20Final%20Version.pdf

110 http://www.gobankingrates.com/savings-account/how-much-physical-cash-need-on-hand-in-case-national-emergency/

The card industry’s sensational claim that cash use implies criminality, whether made explicitly or implicitly, is extremely arrogant and overwhelmingly based upon faulty or biased research. The correlation between criminal acts and cash use has been made many times by individuals with ties to other methods of payment, typically credit and debit cards, to convince central banks and governments to abandon cash.

What this claim does not take into account is the number of unbanked and underbanked individuals and households that rely on cash for everyday transactions, as well as stored value. Central bank payment studies from around the world, including the New Zealand study referenced below, have clearly shown that a majority of people continue to use cash every day for a number of perfectly legitimate and logical reasons, whether they be emotional, historical, or logical. In times of uncertainty, there is no equal to cash as a stored value.

A 2010 consumer study by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, recently presented at a Currency Conference, found that only 5% of New Zealanders did not hold cash. 102 The conclusion that 95% of New Zealanders are criminals or engaged in criminal behaviors would be false!

For unbanked and underbanked individuals, as defined below by Martha Perine Beard in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Central Banker, cash is a must for day-to-day living:

REACHING THE UNBANKED AND UNDERBANKED

The word unbanked is an umbrella term used to describe diverse groups of individuals who do not use banks or credit unions for their financial transactions. They have neither a checking nor savings account.

Some consumers are unbanked for a variety of reasons. These include: a poor credit history or outstanding issue from a prior banking relationship, a lack of understanding about the U.S. banking system, a negative prior experience with a bank, language barriers for immigrant residents, a lack of appropriate identification needed to open a bank account, or living paycheck to paycheck due to limited and unstable income.

The most common groups of unbanked persons include low-income individuals and families, those who are less-educated, households headed by women, young adults and immigrants. As part of the Census Population Survey sent nationwide in 2009, the FDIC asked finance-related queries to help build the database on household banking habits. Responses showed that almost one in 10 households do not use a bank at all. When compared with the 9 percent estimate gathered in the 2001 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, the percentage of unbanked consumers appears to have remained relatively stable. The survey further estimated that nearly 9 million households (approximately 7.7 percent of the population) are unbanked. 103

A sizeable percentage of the global population does not have a bank account or use formal financial services. Currency Research looks at the numbers of unbanked and underbanked individuals in the US and around the world.

The 2011 US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households found that over 28% of US households are considered unbanked or underbanked and 42.9% have used alternative financial services (AFS):

At least 42.9 percent of all U.S. households have used one or more of the following types of AFS: non-bank money orders, non-bank check cashing, non-bank remittances, payday loans, pawnshop loans, rent-to-own agreements, and refund anticipation loans. About 54 percent of all households have never used these services. In 2009, 35.7 percent of all U.S. households had used AFS, and about 60 percent had never used these products (though data on household use of non-bank remittances were not collected in 2009). 104

Forbes reported on the FDIC survey cited above in 2013:

Nearly one-third of the U.S. population—106 million people—are either underbanked or unbanked, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). That means they don’t have bank accounts or regularly make non-bank financial transactions. One in five households has zero or negative assets. Twenty-five million have no credit score, which makes them invisible to the mainstream U.S. financial system. 105

Central Banker reports that the percentage of unbanked individuals has remained relatively constant at 9% of the total American population from 2001 to 2009. 106

According to a 2011 World Bank survey, over 2.5 billion people around the world are unbanked (this figure does not include the underbanked):

Three quarters of the world’s poor don’t have a bank account, not only because of poverty, but the cost, travel distance and amount of paper work involved in opening an account, according to new data released by the World Bank.

About 25% of adults earning less than $2 a day have saved at a formal financial institution, according to the 2011 survey of about 150,000 people in 148 countries. The problem of being “unbanked” is also linked to income inequality: the richest 20% of adults in developing countries are more than twice as likely to have a formal account as the poorest 20%, according to the data collected by Gallup, Inc. for the World Bank’s Global Financial Inclusion Database. 107

The infographic on the following page presents data about the world’s unbanked sourced from the World Bank’s Global Findex, a global financial inclusion database that measures the use of financial services and identifies the unbanked, a category which includes those who experience the greatest barriers to access. 108

According to the Central Bank of Ireland’s 2013 National Payments Plan, the unbanked in Ireland include a range of financially excluded groups that rely on cash on a daily basis for a variety of legitimate reasons:

Financial Exclusion

Sections of Irish society may find it difficult to make the transition to electronic forms of payment from the traditional paper based methods such as cash.

The two key issues here relate to financial exclusion and barriers to electronic payments. For many, the problem is one of financial exclusion.

One fifth (20%) of Irish households do not have a current account and low income has the biggest impact on being financially excluded

Low income consumers (whether banked or unbanked) face a number of barriers in using electronic payments which remain a less attractive proposition than cash based money management.

This is because a cash budget offers low income consumers control, certainty, flexibility and visibility as they can see their money and keep track of their spending on a daily and weekly basis. Conversely, low income consumers fear that if they use electronic payments they could end up spending too much, they are not able to earmark income and they cannot keep track of their finances. Lack of security and fear of fraud also present a real barrier to moving away from cash. Low income consumers face particular barriers in relation to direct debits as they do not suit their weekly budgeting cycle, they fear losing control of their finances and direct debits offer little flexibility. Low income consumers also fear going into debt or unauthorised overdraft as this could incur default charges. Similarly, debit cards can make low income money management difficult as it can be hard to keep track of what is spent, money cannot be earmarked, and often small amounts of money cannot be withdrawn from ATMs.

Furthermore, using cash-back facilities requires something to be purchased, which may be an unnecessary extra expense, and there is sometimes a small charge on low value debit card purchases.

Elderly: There are groups of older people for whom changing to modern payment methods may tend to be difficult, impractical and/or problematic. This includes those who do not currently have a current account and for whom cash is their only form of payment method, those who do not have IT skills, those on very low incomes, and those with reduced mental capacity.

Members of the Travelling Community: Many Travellers on low income who have never operated a bank account will have extreme difficulty in managing a low income electronically

People in Debt: A concern was expressed is that if people in debt used electronic transaction methods rather than cash that all income they would receive or generate would be offset in the first instance against any overdue debts they may have

People with low levels of financial awareness: Such people may not understand how to budget and deal with their finances in a manner that will keep their debt to a minimum

Rural Dwellers and people in outlying, peripheral urban areas: People living in rural Ireland whose only financial transactions take place in shops, post offices and other services which do not currently cater for electronic transactions. In addition the availability of appropriate and secure ICT infrastructure direct to the home, particularly in older properties and in rural locations, can be an issue.

People with low literacy and numeracy: People with literacy and numeracy challenges may have difficulty or need support with reading terms and conditions and statements related to transactions and banking. Issues with numeracy may be more difficult with the absence of ‘cash in hand’, which is more tangible and ‘see able’ than electronic money

People with limited computer literacy and computer access: Anybody who is not computer literate or without the appropriate equipment will find it very difficult to make a change. This would include older people, but also households without access to a home computer or smartphone

Migrants: Migrants and minority ethnic groups may face particular challenges with regard to lack of knowledge of the Irish financial services system, language issues, and religious issues regarding financial services. 109

In times of economic upheaval, cash remains indispensible as a stored value. As shown in the article below, American financial advisors advise clients to hold as much as eight months’ worth of living expenses in cash at all times:

HOW MUCH PHYSICAL CASH DO YOU NEED ON HAND IN CASE OF A NATIONAL EMERGENCY?

Picture this: You’re fast asleep one night when suddenly, you’re abruptly woken up by the sounds of a raging Martian attack on Planet Earth. The aliens have raided the world’s banks and obliterated every ATM with their radioactive lasers, so you have no access to your savings account.

To make matters worse, there’s also a zombie apocalypse happening at the same time, and you’re forced to flee your home, on the run in the dark night, with little in the way of resources to stave off the monsters. How much physical currency would you need to survive?

Part of being prepared for any contingency, big or small, is having a reserve of emergency cash at your disposal at all times.

Despite what many sources say, there’s no magic amount you should have nestled away in your emergency fund. Some say $500, others $1,000. Still others suggest three to six months of pay. Suze Orman’s magic number is eight months of living expenses. You might aim for a conservative $10,000, or more.

You should do what feels right to you. No matter the amount, an emergency fund is absolutely necessary — make it a priority. In fact, financial gurus like Jim Wang of Bargaineering, or Dave Ramsey say to build up your own reserves fully expecting an emergency: “It’s not a matter of if these events will happen,” Ramsey says, “it’s simply a matter of when.” 110

To underscore this point, the chairman of Currency Research opened the 2013 Currency Conference in Athens with the slides below. The slides detail the chairman’s recent personal experience in Cyprus on the day the banking system failed and cash became king for months:

In times of economic crisis when banks, electrical, and even mobile systems fail, cash is the only truly reliable method of payment. For contingencies on how to move cash and maintain economic stability during such upheavals, central banks are among the most prepared institutions in the country. Unfortunately, there are many recent and historical examples of the role of central banks in averting economic meltdowns.

Currency Research disagrees with the sensationalist and false claim that cash use implies criminal behavior. Diverse groups of people use cash for a range of legitimate reasons, as noted in the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s 2010 consumer study cited above, with large denominations typically reserved for stored value and small denominations used for everyday transactions.

This article has been posted with permission from Currency Research and is excerpted from The Case for Cash Part 1: Myths Dispelled. To request a copy of the full report or to learn more about Currency Research, please click here.

102 http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/notes_and_coins/banknote_upgrade/4436446.pdf

103 https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/cb/articles/?id=2039

104 http://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2013_AFSAddendum_web.pdf

105 http://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2013/06/14/banking-the-unbanked-a-how-to/

106 https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/cb/articles/?id=2039

107 http://go.worldbank.org/72MAKHBAM0

108 http://go.worldbank.org/QMN11VEEX0

109 https://www.centralbank.ie/paycurr/paysys/Documents/National%20Payments%20Plan%20-%20Final%20Version.pdf

110 http://www.gobankingrates.com/savings-account/how-much-physical-cash-need-on-hand-in-case-national-emergency/

Additional Resources from ATM Industry Association

- 4/26/2024 - Time to Take Action! Support the Crime Bill - We Need You!

- 4/23/2024 - ATMIA Unveils Strategic Collaboration with Reconnaissance International to Elevate Intelligence & Networking Services to the ATM & Currency Industries

- 4/21/2024 - Fight Against Cashless Economy:

- 4/18/2024 - 3 myths about accepting cash at self service

- 4/18/2024 - Upcoming ATMIA/ASA Committee Meetings: April and May 2024

- Show All ATM Industry Association Press Releases / Blog Posts